Disclaimer: this may provoke…

“We may indeed be living in a new golden age of theatre, but even if we are, I would still like to think that, lurking in a dark alleyway round the back of every new £15 million glass-and-steel culturally non elitist Shopping Mall Playhouse and Corporate Entertainment Facility, is a gobby and pretentious twenty-year-old with a Passion for real theatre, a can of petrol and a match.”

Mike Bradwell in ‘The Reluctant Escapologist’

Yesterday I attended the first of the Warwick Commission’s Provocations on The Future of Cultural Value. With the case presented by Robert Peston about the economic value of the culture, I decided to share my thoughts around marrying both the economic and holistic arguments – if we look at major arts philanthropists in the UK their giving isn’t fueled by one or the other; it’s fueled by both.

As I sat on this thought, the discussions that arose from the audience were similar to ones I’ve heard time and time again – how do we diversify our audiences? Where are the young people on the panel? How do we engage more people beyond the sector in this debate?

So I decided to share my experience; as a young person, as a loving and adoring spectator, as a person who has recently completed studying in both secondary and higher education, as an employee of the sector and as a theatre-maker. My contribution was the following (paraphrased slightly from an adrenaline fueled nervous memory bank):

“I’m Dana. I’m a young person. And I’ll gladly sit on any future panels should you need me to. I’m a theatre maker – and I saw my time at university as my artist development phase. I wasn’t subsidised for this – although I received a loan from the government I’ll be spending the rest of my life paying that back. I was never taught how to source funding, write an ACE application, and look for trusts and foundations at university. I love making theatre and I’ve never been paid for it, the irony being that I actually now work as a fundraising fellow in the arts, on a scheme funded by the ACE. My thought to the panel is this: the economic and holistic arguments are continuously separated – is there a way of joining these together? If we look at major arts philanthropists in the UK, their giving isn’t fueled by one or the other, it’s fueled by both.”

What I felt my contribution addressed was the following thoughts/questions:

a) Unlike most other sectors, we are as a majority, both producers and consumers – as I said above I am an audience member of, I’m an academic of, I’m an employee of and I’m a creator of art & culture in the UK. I’m involved in every possible facet. We create our supply and demand. How productive is talk about audience development and diversification if, quite frankly, we are the majority of our audience? How productive is it to sit these passionate people who are invested with their entire lives in the sector that it’s not worth asking the government for more money, and that we need to find another way to articulate our value?

b) Arts education is extremely important and valuable, but it needs to be more varied. If we want artists to be paid for their art, we need to make sure that they are equipped with the confidence and belief in themselves to ask for it, understand how to source funding, and understand how to make it sustainable. How do we do that?

c) My actual question: can we join the arguments about the holistic and economic values of the arts?

To my dismay, this is what Twitter took from my contribution:

The first, from @Abi_Gilmore:

Can you believe it?! A GENUINE YOUNG PERSON! And no Steven, I’m not a son or daughter of a panel member.

The second, from @MariaBarrat:

Whilst I’m delighted that I wasn’t referred to as a genuine young person this time, I wasn’t taking about college. Over my three years of study had to sustain a roof over my head by having two part-time jobs and getting the odd £50 food shop from my parents throughout my university degree. Despite my misleading name, appearance and accent I’m not actaully White British and middle class.

I spent every last penny I had on theatre books and theatre tickets. I actually went without food for two days so I could afford to go and see Punchdrunk – true story.

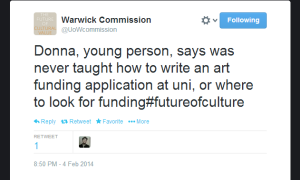

The final kick in the teeth, from @UoWCommission:

DEAR WARWICK COMMISSION – THAT IS NOT MY NAME!

This summary was also not the point of my contribution: I didn’t address the panel to talk negatively about my university experience – my degree programme was wonderful and made understand me how to identify value within the arts and culture. It developed my work ethic, and it provided me with a place to meet like-minded people who I’ve gone on to work with creatively since.

No wonder the sector doesn’t engage young people’ in this discussion. This was hardly the first event that I’ve attended with a similar format: the key note speech, the panel discussion, the Q&A… followed by networking wine & canapés. This isn’t a format that is going to engage a diverse audience. If anything, and I can confidently speak on behalf of a lot of young people at these events (because I’m normally huddled in the group with them), I felt extremely intimidated by that situation. There are so many artists and young people who don’t consider themselves part of the ‘sector’. We’re all creative folks – there has got to be a more creative way that we can engage different people in this discussion.

The value of culture to me is semantically understood by the way it has shaped me as a person: my experience, my hobbies and passions, and my professional life. What’s made and shaped my experience? Well, a big part of this has been working at the Roundhouse.

As a sector we use the terms ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘marginalised’ to describe young people far too often. It’s not that I don’t agree that we’re not at a disadvantage or that we aren’t marginalised because we are. The Princes Trust published a report this year which highlighted that 1 in 10 young people feel they have nothing to live for – and there have been times in my life I’ve identified with that feeling.

There are many social care & social justice charities and organisations that work with disadvantaged young people in an impactful way talking through their problems with finances, domestic issues, bullying… And yes, as highlighted in the debate, so many artists are more worried about welfare cuts than they are about arts cuts. I’m not devaluing those services – but what culture does is give young people a reason not just to live, but to enjoy living. That’s why it’s so important.

A great example of this is the Roundhouse – it lets “young people” enjoy the freedom of creativity through access to artists, equipment and space. It’s from that freedom that they develop the skills that we talk about as a sector – team work, confidence building, technical and artistic skill etc… as a theatre maker, and there is no better feeling than that of an artistic discovery or development in the rehearsal room. This is quantifiable value. This in small, regular measures is the best confidence builder I know.

At the Roundhouse young people are treated not like professionals but as professionals. We aren’t treated as young people with disadvantages – everyone is given a level playing field through equal opportunities and endless resources – and because the Roundhouse says “look this is all yours, do what you want with it” that’s why people thrive here – we have the space and time to develop as professional artists and sector employees.

I don’t think the entire focus should be on young people of course, but I do strongly believe that those of us who are young artists, audiences and employees of the sector can really help in shaping these conversations.

It’s my time to take that can of petrol and strike the match. I’d like to leave you with this final proposal if you will…

I can gather 50 young people who are cultural contributors from VERY diverse backgrounds and disciplines. They are not all from London. Some have government funding and some don’t even know it exists. All of these people are producing cultural output that is accessed by non-middle class white audiences. All of these people can name at least five other cultural outputs that have inspired them to do what they do.

Meet with us. Let us be a part in helping to shape the future of cultural value. Get us on those panels. Commission us to respond to this question. Introduce us and get us talking to the right people. Give us half an hour, a room and a microphone to talk to those we need to convince that culture has an incredible value.

With the greatest love and respect,

Dana Segal